Title of paper under discussion

Preservation of musical memory in an amnesic professional cellist

Authors

Carsten Finke, Nazli E. Esfahani and Christoph J. Ploner

Journal

Current Biology, Volume 22, Issue 15, 7 August 2012, Pages R591-R592

Link to paper (free access)

Overview

Is musical memory housed in the same brain region(s) as other types of memory? The answer, according to the authors of this paper, is not clear from previous scientific literature – or, as they put it: “the degree of independence of such a system [musical memory] from other memory domains is controversial”.

Step forward a 68-year old German cellist (known by his initials ‘PM’) with permanent and severe amnesia following a bout of encephalitis, who volunteered to be tested in the name of investigating this very question. Despite being unable to name a single German river or chancellor, PM performed as well as other musicians in various tests of recognition memory for music, suggesting that the learning and retention of musical information depends on brain networks distinct from those involved in other types of memory.

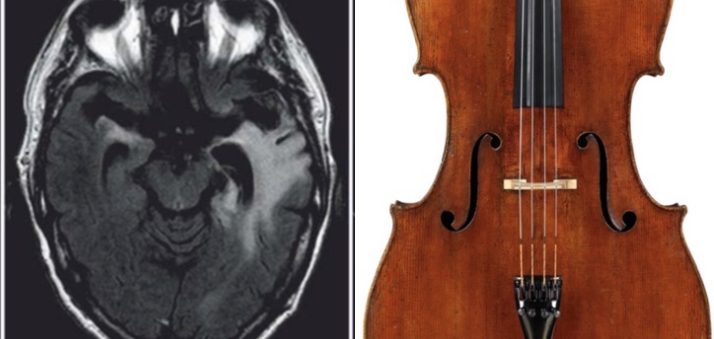

The patient

At the start of this paper, written in 2012, we learn that “throughout his career, PM had performed in major German orchestras and had gained a wide repertoire that ranges from early to contemporary music.” In 2005 he was affected by herpes encephalitis – inflammation of the brain caused by the ‘cold sore’ virus – which caused lesions in specific regions (the right medial temporal lobe, large portions of the left temporal lobe and parts of left frontal and insular cortex). He was left with severe amnesia, both in his ability to recall past memories (‘retrograde amnesia’) and his ability to lay down new memories (‘anterograde amnesia’). So, for example, in their initial tests “he could not remember the name of any German river or chancellor. He was neither able to report biographical details from childhood, youth or adulthood, nor other personal or professional events. PM had no memory of relatives and friends, except for his brother and his full-time caregiver. He was unable to recall or recognize lyrics of well-known folk and children’s songs. PM could not recall any famous cellist and remembered the name of only one composer (Beethoven). However, PM was still able to sight-read and to play the cello.”

Method, Results and Discussion

With initial investigations revealing “exceedingly poor performance” in standard (non-musical) memory tests, the research team moved on to look at PM’s music perception skills. These were found to be ‘normal’, including – surprisingly – his ability to remember single phrase melodies.

To investigate further whether musical memory was “truly intact” in PM, the team “devised three tasks that took the onset of his amnesia into account”. In order to compare his performance against those of other musicians they recruited 10 age-matched volunteers as controls: 5 string-players from the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra and 5 amateur musicians.

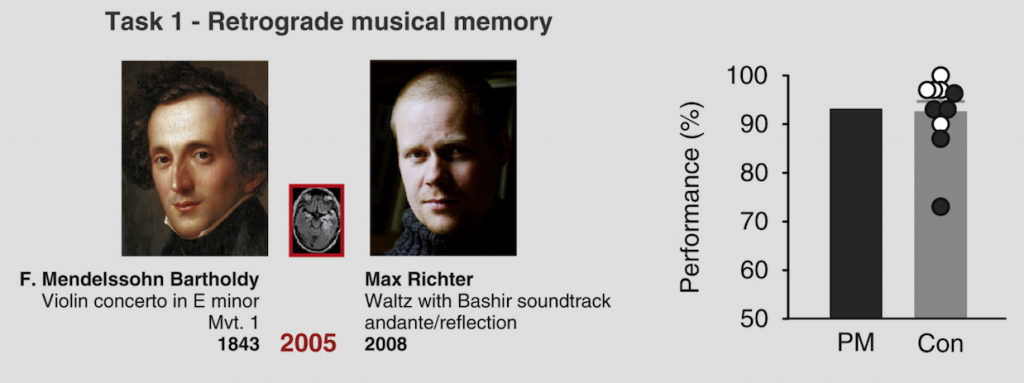

Task One – (a test of retrograde musical memory)

PM (and each of the control participants) listened to “excerpts of well-known instrumental music composed before 2005 — so before the onset of PM’s amnesia — paired with excerpts of instrumental music composed after 2005.” After listening to each pair, the participant was asked which excerpt sounded the more familiar.

Each pair of pieces (one pre-2005, one post-2005) was closely matched for musical character and musical line-up. It was very unlikely that PM had heard any of the post-2005 excerpts before as he sadly stopped listening to music after his illness.

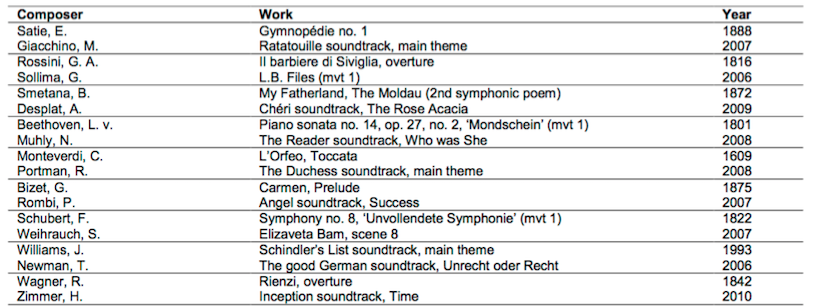

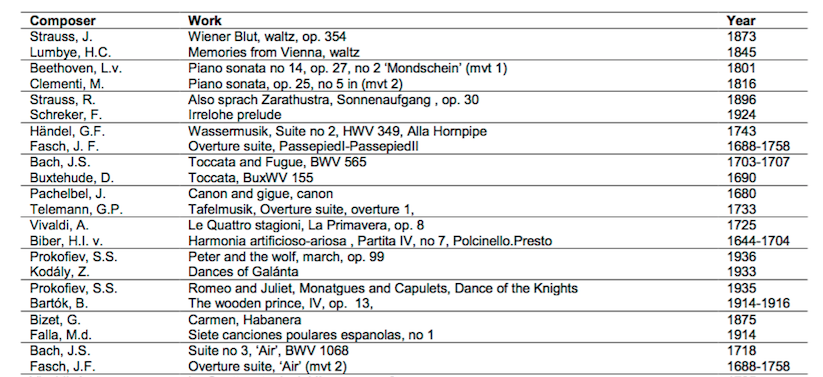

Here are some examples of the pairings, with the date of composition of each excerpt:

As shown in the following graphic, using one of the pairs as an illustration, PM scored as well as the controls on this task, correctly identifying the pre-2005 music as more familiar 93% of the time (compared with the controls’ average of 92%):

The research team concluded that PM was indeed successfully recalling pieces he had heard before the onset of amnesia, recognising them as familiar compared with pieces he had never before heard.

Perhaps though, they reasoned, he was merely discriminating contemporary music against older music. Hence they devised a second task…

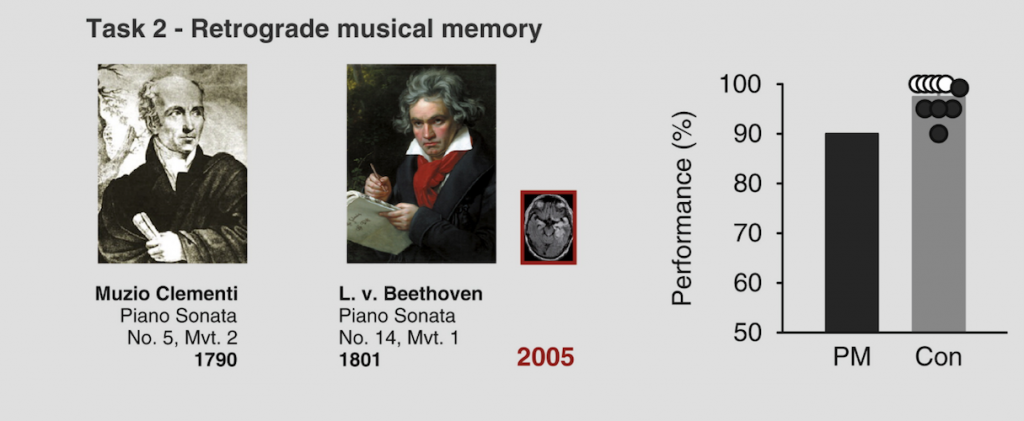

Task Two – (another test of retrograde musical memory)

As in Task One, Task Two involved participants listening to pairs of excerpts and being asked which was the more familiar. In contrast to Task One, however, the excerpts were both from the same musical period as well as being closely matched for musical character and musical line-up; the crucial difference between them being that one was well-known, the other obscure.

Here are some examples of these pairings, again with the date of composition of each excerpt:

Once more PM performed pretty much as well as the controls. The researchers reported that “although PM’s continuous involvement with music had ceased since his encephalitis, he still discriminated famous from non-famous pieces at a level similar to controls” – 90% compared with an average of 97%, as shown in this graphic:

So PM, who had displayed a severe inability to recall non-musical memories was, in contrast, able to recall musical memories – in other words his retrograde amnesia did not seem to include his recall of music.

How about his ability to lay down musical memories? Had this ability survived the effects of encephalitis in the same way as the recall of musical memories seemed to have done? To test for ‘anterograde amnesia’ a third task was devised…

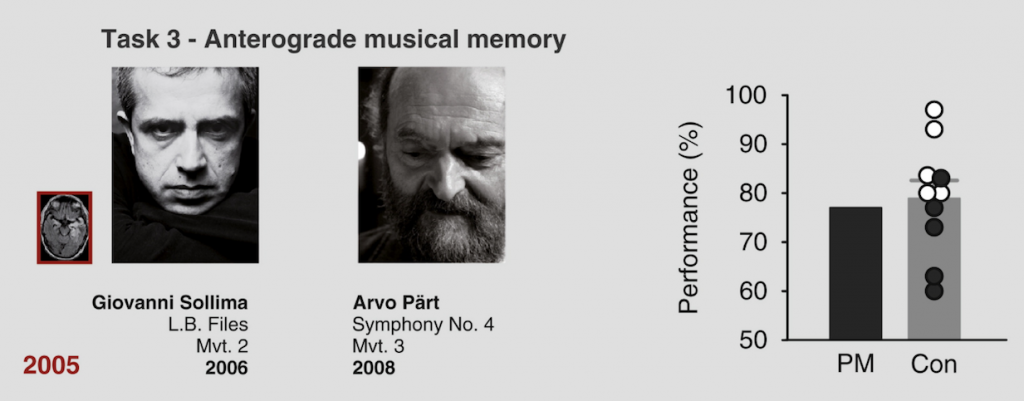

Task Three – (a test of anterograde musical memory)

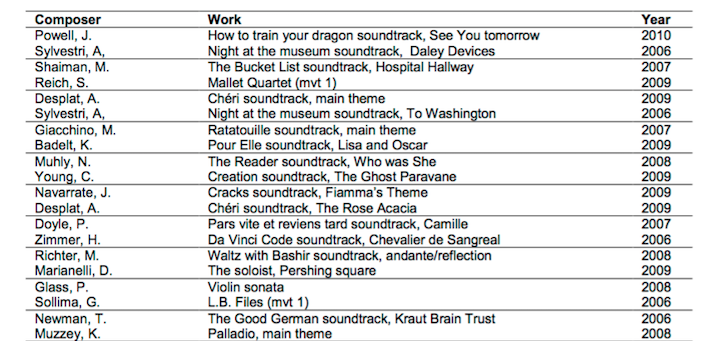

In this task each participant listened to a series of individual excerpts composed after 2005. 90 minutes later they were presented with a series of pairs of excerpts, each pair containing one of the excerpts they’d heard 90 minutes earlier and one novel excerpt (though matched in musical character and line-up). They were asked to nominate which excerpt of the pair was the one they’d heard 90 minutes ago.

Here are some examples of these pairings, again with the date of composition of each excerpt:

Once more, PM performed at the same level as the controls (77% against an average of 79%):

In conclusion so far, Finke and his colleagues found that “PM’s performance in these musical memory tests was at the same level as a control group composed of amateur and professional musicians”.

Was this intact memory specifically musical, or was it non-verbal memory in general that the encephalitis had spared? To investigate this question, the researchers looked at his memory for a) faces and b) objects.

In the faces task, similar to Task Three above, each participant (PM and the 10 controls) was presented with a series of individual faces and then 90 minutes later was presented with a series of pairs of faces – one taken from the series presented 90 minutes previously and one completely novel but similar – and asked to identify the recently seen one. PM performed significantly worse than the control participants (achieving 55% correct identification compared with an average of 91% by the controls).

In the objects task, again similar to above, each participant (PM and the 10 controls) was presented with a series of individual objects and then 90 minutes later was presented with a series of pairs of objects – one taken from the series presented 90 minutes previously and one completely novel but similar – and asked to identify the recently seen one. Once more PM performed significantly worse than the control participants (achieving 50% correct identification compared with an average of 99% by the controls).

All in all, it seemed that PM ability to lay down and recall musical memories was spared by his encephalitis; or, in the words of the authors, “in patient PM, learning and memory of complex musical information constitute an island of intact cognition within a severe amnesic syndrome.”

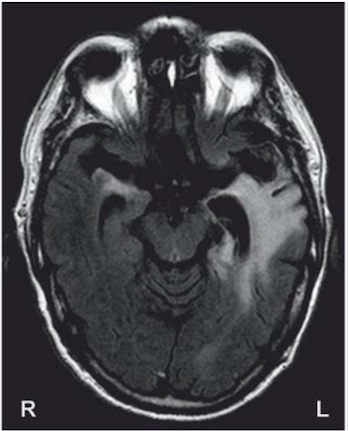

Finally, Finke and his colleagues consider the areas of PM’s brain they know from scans to be damaged (namely the right medial temporal lobe, large portions of the left temporal lobe and parts of left frontal and insular cortex). They note that none of these brain regions, according to previous scientific studies, are associated with the ability to remember musical pieces.

They also quote other research, this time into Alzheimers and dementia patients, revealing that in some patients musical memory impairment and other types of memory impairment coexist, whereas in others there is relative preservation of musical knowledge despite loss of other memories. The findings in PM, they argue, “show with particular clarity that the representation of music in the human brain is distinct and largely independent from other explicit memory modalities.”

By comparing PM’s brain scans with data from other studies, the authors conclude that the rostral (front), rather than medial, part of the right temporal lobe mediates musical memory.

Finke concludes by speculating that it may be music’s role in the development of language that drove humans to evolve a dedicated musical memory system in the brain. He also celebrates the idea that patients with compromised memory functions whose musical memories are however left intact might not only enjoy those musical abilities but also use them to help meet non-musical everyday challenges.

Coda

Moonlight Serenade – Glenn Miller

The 12 cellists of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra