Title of paper under discussion

Tuning in to musical rhythms: Infants learn more readily than adults

Authors

Erin E. Hannon and Sandra E. Trehub

Journal

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA (PNAS), vol 102, no 35, pp 12639-12643

Link to paper (free access)

Overview

A 6-month-old baby is remarkably ‘culture-general’ in perception, able to discriminate speech sounds in languages it’s never heard and faces of species it’s never before seen. By the age of 12 months, an infant’s perception has become more culture-specific, successfully differentiating human faces – and sounds from its own language – but not so easily discriminating non-human faces or non-native languages.

Does such culture-specificity in 12-month-olds hold for music as it does for language and faces? And if so, can these infants then be easily trained to ‘understand’ a new musical language?

Research had already shown that 6-month-old babies from North America could easily distinguish rhythmic variations in music from a foreign (Balkan) culture – suggesting they are musically ‘culture-general’ – whereas North American adults, more ‘culture-specific’ having grown up with Western music, struggled with the same task. In this paper authors Hannon and Trehub discover that by the age of 12 months North American babies can no longer discriminate Balkan rhythms – suggesting they have lost their musical ‘culture-generality’ – but that by listening to Balkan music in the weeks prior to the experiment their task performance was much improved. In contrast, North American adults who listened to Balkan music prior to the experiment showed no such improvement at the task, suggesting that there may be “a sensitive period early in life for acquiring rhythm […]”

Experiments

The research comprised three experiments:

Experiment one

Aim

To discover if 12-month-old North American babies notice modifications in the metre of Balkan tunes and/or Western tunes

Method

52 infants, all aged around 12 months, were split into two equal groups: Group One was to be tested with Western tunes, Group Two with Balkan tunes. Sitting on a parent’s lap in front of two monitors, one to their left and the other to their right, each infant was familiarised with a tune by listening to it four times over, each time accompanying a visual portion of a documentary film on a monitor, and with each repetition coming alternately from the right and left monitor. Group One infants were thus familiarised with a Western tune, Group Two with a Balkan tune.

There followed for each infant a series of variations of that tune, played again with visual accompaniment on alternate monitors, with notes added that either preserved the tune’s rhythmic structure (‘structure-preserving variations’) or disrupted that structure (‘structure-disrupting variations”).

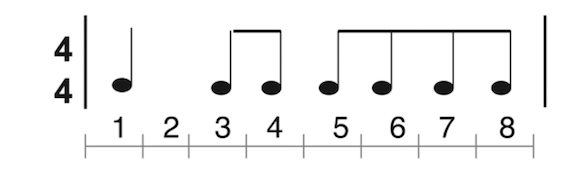

Here is one bar (measure) from a typical Western tune example, presented rhythmically, followed by its ‘structure-preserving’ variation and its ‘structure-disrupting’ variation:

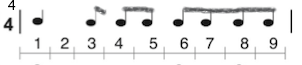

And here is one bar from a typical Balkan tune example, again presented rhythmically, and followed by its variations:

All the while the infant was watched by observers to record the length of time they spent looking at the monitor during each variation. Infants have a ‘typical preference for novel stimuli’ so the researchers reasoned that if a variation was perceived as novel the infant would look at the monitor for longer. Hence, if the infants were perceiving the novelty of metre in the ‘structure-disrupting variations’ then these variations would elicit a longer look than the ‘structure-preserving variations’ (which lacked such novelty).

Results and discussion

Group One (Western tune) infants looked at the monitor for longer during the ‘structure-disrupting variations’ compared with during the ‘structure-preserving variations’. But Group Two (Balkan tune) infants showed no such difference.

This contrasted with similar research (by the same team) on 6-month-old babies, who had spent longer looking at the monitor during structure-disrupting variations of both Western and Balkan tunes.

Put together, this research suggests that 6-month-old infants are perceiving the changes within a structure-disrupted variation – and enjoying the novelty, therefore looking at that monitor for longer – whatever culture it is from. But by the age of 12-months infants can only perceive such structure disruption in music of their own culture.

This finding mirrors research on face and language perception: the ability of an infant to differentiate changes in ‘foreign’ stimuli declines by the end of their first year, but their sensitivity to comparable changes in ‘native’ (or ‘culturally typical’) stimuli remains unchanged.

Experiment two

Aim

To assess whether “brief, at home exposure” to Balkan folk music in the weeks prior to testing might improve the ability of a 12-month-old to perceive the changes in a ‘structure-disrupting variation’ of a Balkan tune.

Method

26 12-month-old infants listened to a 10-minute CD of Balkan music (dance music from Macedonia, Bulgaria and Bosnia) twice a day for 2 weeks before coming into the lab for testing.

Once in the lab they went through the procedure prescribed for Group Two in Experiment One. (The Balkan tunes used in this experimental procedure were not the same as on the CD but were ‘culturally’ similar, ie tunes with the same metrical structure).

Results and discussion

Unlike the Group Two infants in Experiment One, these 12-month-old infants looked at the monitors for longer during the structure-disrupting variations of the Balkan tunes, with the length of the looks matching those of Group One (Western tune) infants in Experiment One.

In the words of the authors, it was clear that “2 weeks of passive, at-home exposure [had] facilitated infants’ differentiation of rhythmic patterns in a foreign musical context”.

Experiment three

Aim

To determine whether at-home exposure to Balkan folk music in the weeks prior to testing might improve the ability of an adult to perceive the changes in a ‘structure-disrupting variation’ of a Balkan tune.

Method

40 college students were divided into two groups. Group A were asked to listen to a 10-minute CD Of Balkan music twice a day for 2 weeks prior to testing. Group B received no such CD.

On testing day all the students underwent a procedure similar to that for infants in Experiments One and Two. But they were all presented with both Western and Balkan tunes, each of which was followed by its relevant ‘test stimuli’ (structure-preserving and structure-disrupting variations). And instead of sitting on a parent’s lap and watching a screen, our adults listened to the music on headphones and rated how similar those ‘test stimuli’ were to their original Balkan or Western tunes.

Results

Unsurprisingly these North American students were better at detecting structure-disrupting variations in Western music than in Balkan music. Indeed, with the Balkan music the strong tendency was to claim that the structure-disrupting variations were more, not less, similar to the original tune than the structure-preserving variations!

And Group A students, although showing slight improvement at the Balkan music task after two weeks of listening to that culture’s music, still didn’t score higher than chance levels in detecting structure disruption, leading the researchers to conclude that “adults failed to attain native-like performance [in the Balkan task] after exposure to foreign musical structures [2 weeks listening to the Balkan CD], in contrast with 12-month-old infants…”

Conclusion

Hannon concludes that “[t]aken together, experiments 2 and 3 indicate that adults do not learn about foreign metrical structures as readily as do infants” and continues to remind us that this is mirrored in other perceptual domains: “[a]dults also have difficulty differentiating nonnative speech sounds […] and faces from unfamiliar racial groups […] even after extensive experience with foreign speech and faces.”

The final sentences of the paper argue for music to be ranked alongside speech and face-recognition when discussing early psychological development. Hannon refers to “‘‘sensitive’’ periods during development, when learning is particularly rapid and behavior is modified easily”, and she continues: “Our findings indicate that such processes are not specific to language or to faces but extend to other domains such as music. Early learning about faces and voices is often viewed as evidence of their social and biological significance. Music must be added to the list of socially and biologically significant stimuli, or it must be acknowledged that the phenomenon of rapid perceptual attunement coupled with early flexibility is more widespread than is currently believed.”

Coda