Title of paper under discussion

Music improves sleep quality in students

Authors

László Harmat, Johanna Takács & Róbert Bódizs

Journal

Journal of Advanced Nursing, vol 62, issue 3, pp 327-335 (May 2008)

Link to paper (free access)

Overview

Nearly 100 Hungarian students with sleeping complaints were divided into three groups. Two of the groups were prescribed a three-week course of bedtime listening – relaxing classical music for Group One, and an audiobook for Group Two – whilst participants in Group Three (controls) were given no such interventions. The students’ sleep quality and mood symptoms were measured before, during and after the study.

Only the group listening to music at bedtime exhibited a significant improvement in sleep quality and in mood, leading the researchers to conclude that “relaxing classical music is an effective intervention in reducing sleeping problems” and that “nurses could use this safe, cheap and easy to learn method to treat insomnia”.

Background

Previous research had identified positive effects of music-listening on people’s quality of sleep, maybe via muscle relaxation, distraction from thoughts, or a reduction in sympathetic nerve activity, anxiety, blood pressure, heart rate or respiratory rate.

But this improvement in quality of sleep was – Harmat and his team reasoned – perhaps merely due to those people having something relaxing to listen to, or feeling positive about taking part in a study that promised a possible insomnia cure. To investigate these various possibilities our researchers included two extra groups – in addition to Group One who listened to relaxing music – in their study: Group Two, who listened to a relaxing audiobook, and Group Three, who received nothing and therefore didn’t have the promise of a possible insomnia cure.

If it was the music itself, rather than relaxing-listening or the expectation of an insomnia cure, helping with quality of sleep, then – according to Harmat and his team – Group One should be the only group to enjoy an improvement in sleep quality.

Method

Ninety-four students, 73 women and 21 men, all within the age range of 19-28 and reporting as suffering from sleep complaints, were recruited from a Hungarian University. After random assignment to one of three groups, each participant awaited further instruction.

Listening material

Members of Group One, the music group, were given a classical music CD, “a collection of relaxing classical music including some popular pieces from Baroque to Romantic (The Most Relaxing Classical, 2 CD, Edited by Virgin 1999)”, with the instruction that “they were to listen to it for 45 minutes every night at bedtime for 3 consecutive weeks.”

Members of Group Two, the audiobook group, were given a CD containing “11 hours of short stories by Hungarian writers such as Frigyes Karinthy, Gyula Krúdy, Géza Gárdonyi, Zsigmond Móricz and Mihály Babits”. As with their colleagues in Group One they were “asked to listen to the audiobook at bedtime for 45 minutes each night for 3 consecutive weeks” – same stories every night or different ones, their choice.

Group Three participants, the controls, received no such listening interventions; rather they were asked to avoid music or audiobooks at bedtime.

Monitoring the effects of listening-material on sleep

Quality of sleep and mood/depression were monitored as the three week experiment progressed.

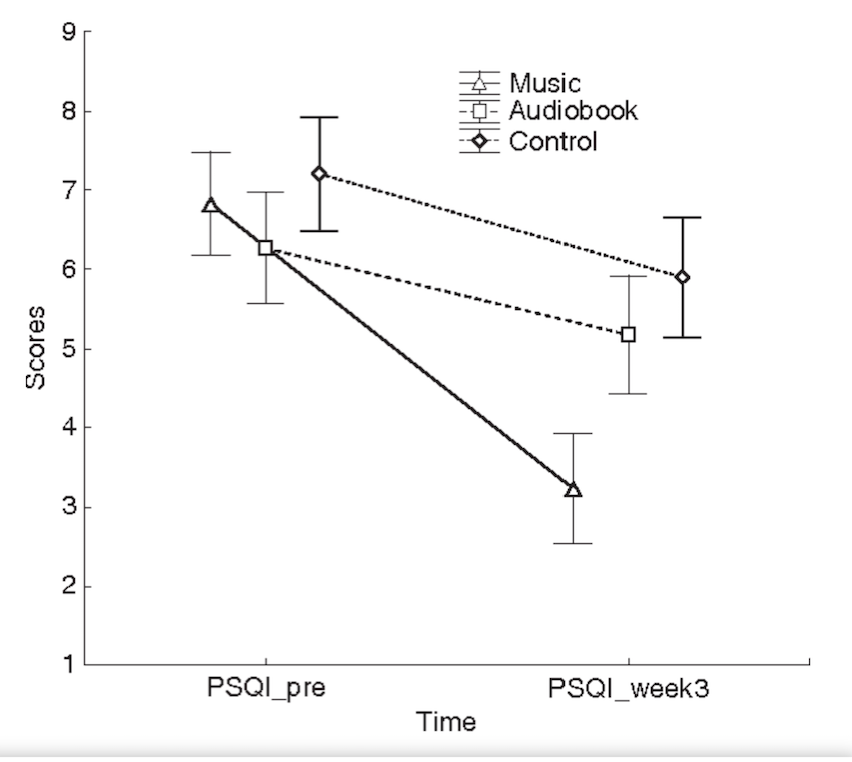

To determine sleep quality the researchers used a standard questionnaire, the Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), that measures self-reported sleep habits, giving information “about the participant’s perceived sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbance, daytime dysfunctions and use of sleep medication.” Overall scores range between 0 and 21; the higher the score, the worse the sleep.

For Groups One and Two these PSQI measures were taken once before the three-week experiment, and then once at the end of every week during it – four readings each in total. For Group Three PSQI was taken twice, once before and once after the three-week experiment.

To determine depression/mood the participants were handed a series of questions called the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), assessing “the existence and intensity of the following depressive symptoms: social withdrawal, inability to make decisions, sleep problems, fatigue, exaggerated anxiety over somatic complaints, inability to work, pessimism, lack of satisfaction, difficulties with feeling pleasure and self-blame.” Scores range from 0 to over 60; the higher the score, the worse the depression.

Groups One and Two had these BDI measures taken once before the three-week experiment and then once more after it – two readings each in total. Group Three only had BDI taken once, before the three-week experiment.

Results

Analysis of the PSQI (sleep quality) data revealed that listening to music (Group One) significantly improved sleep quality, and listening to audiobooks (Group Two) or no listening intervention (Group Three) had no such significant effect. And the improvement continued week on week during the study, suggesting that “listening to music has a cumulative effect on sleep quality.”

Another way of characterising these data was to divide participants – all 94 of whom started with poor PSQI scores of ‘6 or over’ – into ‘responders’ (those whose PSQI scores improved, dropping to ‘under 5’ post-treatment) and ‘non-responders’ (those who remained poor sleepers). By the end of the study, 86% of Group One (music listeners) were shown to be responders, compared with only 30% of Group Two (audiobook listeners).

Depressive symptoms, as measured by BDI, decreased in Group One (the music listeners) but not in Group Two (audiobook listeners). But no claim could be made that improvement in mood was due to improvement in sleep quality.

Discussion

In addition to the group of bedtime music-listeners, this study included a group of audiobook-listeners (who were relaxing, but not through music) and a group of non-listeners (who were taking part but without any listening intervention that might lead to a hope of sleep quality improvement). Thus, claimed our researchers, this was “the first study [in the world] to show that music per se improves sleep quality by controlling for the confounding effects of relaxation and positive expectations”.

The authors propose reasons as to why music might improve sleep quality. Some research suggests there might be an influence of slow music on heart rate and blood pressure, with one study advising an optimal tempo of 60-80 bpm.

As regards the finding that music also lowered depressive symptoms, our authors remind us of other research pointing to a musically-induced increase in circulating endorphin levels.

In conclusion, the authors write “Our findings provide evidence for the usefulness of relaxing classical music as an intervention for sleeping problems in young adults. In line with former studies, we confirmed that listening to relaxing classical music has a positive effect on sleep quality. Hospitalized patients often suffer from sleeping problems, such as insomnia, and listening to music is a simple intervention that may reduce these problems. Nurses should use music therapy in their practice because it is a safe and cheap method which may be used to treat insomnia in different populations. In addition, the intervention is quick and easy to learn.“

Coda

Air from Third Orchestral Suite – Johann Sebastian Bach

Berliner Philharmoniker, cond. Ton Koopman