Title of paper under discussion

Robert Schumann’s Focal Dystonia

Author

Eckart Altenmüller

Journal

Neurological Disorders in Famous Artists (eds: Bogousslavsky J, Boller F) Front Neurol Neurosci. Basel, Karger, 2005, vol 19, pp 179–188

Link to original paper (open access)

Overview

A compelling retrospective diagnosis of the finger problems that saw composer Robert Schumann (1810 – 1856) abandon his promising virtuoso piano career at the tender age of 22.

Author Eckart Altenmüller, a world expert on focal dystonia (‘musician’s cramp’), recognises the causes and symptoms of this disorder in details of Schumann’s life, using his diaries, letters, doctor’s notes and even one of his compositions as evidence. He finds the young composer practising the piano up to “seven hours a day” and becoming increasingly frustrated by the “loss of fine motor control in his right hand” that took place over the years 1829 – 1833.

We learn that Schumann developed an apparatus “to improve the strength of his [right hand] middle finger” – fashioned out of a cigar box – to no avail. The right hand figuration found in his “Study in Double Notes” (the later Toccata op.7) was quite likely “an attempt to find a creative solution to the movement disorder [focal dystonia] through avoiding the use of the middle finger.”

Altenmüller discredits three other theories explaining Schumann’s condition – tendonitis, damage from the cigar box apparatus and arsenic poisoning – concluding that only the diagnosis of focal dystonia fits the biographical evidence.

The final two paragraphs of the paper discuss the possible neurobiological origins of focal dystonia. Some background knowledge will help elaborate the terms “digital representations in the somatosensory cortex”, “lateral inhibition” and “maladaptive brain plasticity” used in the text.

Digital representations in the somatosensory cortex

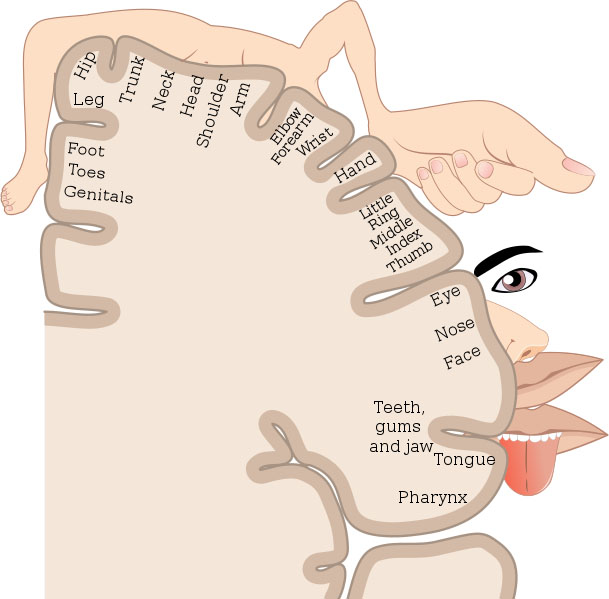

Different areas of the outer layer (‘cortex’) of the brain govern different functions. The area dedicated to the sense of touch (including pain and vibration) is the somatosensory cortex, located in a strip of the parietal lobe. (Movement is governed by the motor cortex, just next door in a strip of the frontal lobe).

Within the somatosensory cortex different areas represent different regions of the body, resulting in a ‘body map’:

In a healthy somatosensory cortex, each representation is discrete; so, for example, each finger (or ‘digital representation’), though lying next to another finger, is still separate from it on the map, without any overlap. In a person with focal dystonia in the hand, these ‘digital representations’ become fused or blurred, “reflected in the decreased distance between the representation of the index finger and the little finger when compared to healthy control musicians.” And when sensory information is blurred, motor actions relying on that information necessarily become confused, hence the dreadful effect of dystonia on musical performance. Such blurring, according to the paper, may be based on “impaired lateral inhibition“.

Lateral inhibition

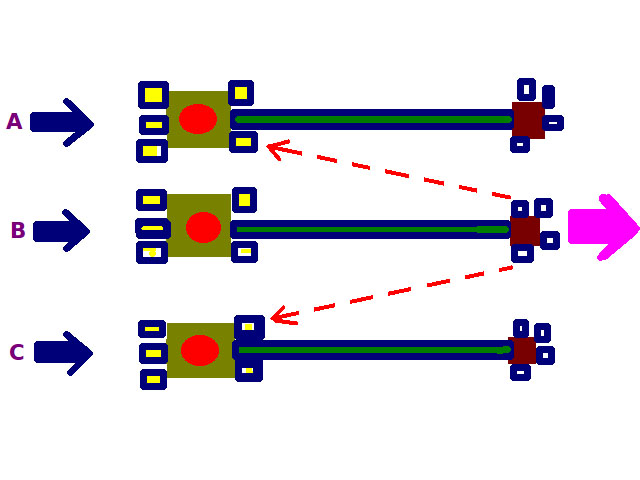

Lateral inhibition is when an active nerve cell inhibits the activity of its lateral neighbours. It acts to sharpen sensations, to heighten them in the area receiving the most stimulation by reducing perception in surrounding areas.

Above: If a signal coming from the left (three blue arrows) activates all three neurons (A, B, and C) but affects B with the strongest signal or first, then B fires rightwards down the axon but also sends signals to neurons A and C (broken red arrow) not to fire. The result is a sharper signal (pink arrow).

In the brain of a healthy pianist, lateral inhibition helps to keep each digital (finger) representation separate and distinct. In the brain of a dystonic pianist, it seems that lateral inhibition breaks down, leading to a blurring of the digital representations:

“Maladaptive brain plasticity”

This blurring, or fusion, of the digital representations in the somatosensory cortex is an example of ‘maladaptive brain plasticity’. All musicians’ brains exhibit plasticity, meaning they adapt in response to their work and environment by strengthening or originating neural connections and pathways. If such plasticity lead to dysfunction, as is the case in the blurring of digital representations found in the somatosensory cortex of dystonic musicians, it is termed ‘maladaptive’.

Conclusion

Robert Schumann’s fortitude in facing this dreadful disorder paid glorious dividends. In the closing words of Altenmüller “For us, Schumann’s decision to follow a career as a composer was a blessing, because it allowed his creative talent be developed to masterful perfection.”

Coda

Toccata in C Major, op.7 – Robert Schumann

Piano – Martha Argerich