Title of paper under discussion

When coloured sounds taste sweet

Authors

Gian Beeli, Michaela Esslen and Lutz Jäncke

Journal

Nature, 434, 38 (2005)

Link to paper (free access)

Overview

Written up in 2005, this ‘short communication’ to the journal Nature describes a professional musician who cannot help sensing tastes on her tongue when she hears musical intervals, with specific intervals consistently producing specific tastes. To test the notion that she was using the tastes to help identify the intervals, the paper’s authors dropped certain tasty solutions on her tongue whilst playing certain intervals through her headphones. She was indeed much quicker at identifying an interval when the taste solution ‘matched’ the interval compared with when the taste solution was ‘incongruent’.

Background

Synaesthesia is the phenomenon whereby a person involuntarily experiences one sensory mode (e.g. colour or smell) whilst being presented with another (e.g. sound). The most common ‘concurrent perception’ is colour, with smell and taste being ‘rare’. Importantly, true synaesthesia is not learned by association; so, for instance, a given colour associated with a certain word by a word/colour synaesthete is not experienced because that synaesthete has at some point seen that word written in, or alongside, that colour. Rather she or he is somehow already ‘cross-wired’ such that they cannot help experience the additional sensation.

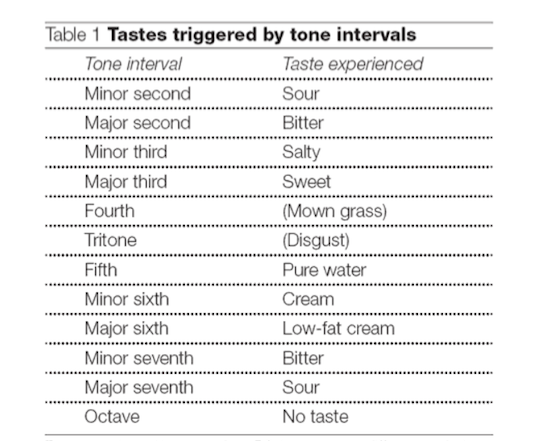

For this research, the authors had already identified a 27-year-old professional musician (known by her initials “E.S.”) with “interval-taste” synaesthesia. Whenever E.S. “hears a specific interval, she automatically experiences a taste on her tongue that is consistently linked to that particular interval”, a type of synaesthesia never before described in the scientific literature. After a year of investigation, the researchers were confident enough, through the consistency of her answers, to compile this table of her specific interval-taste experiences:

The researchers also confirmed that 1) “her interval-to-taste synaesthesia is unidirectional: she does not hear tone intervals when exposed to taste.” and 2) she “applies this synaesthesia in identifying tone intervals”.

For this present piece of research the team of Beeli, Essen and Jäncke were keen to further assess “the influence of E.S.’s synaesthetic gustatory [taste] perception on her ability to identify tone intervals” by using a classic psychological tool – the Stroop test.

Method (Stroop Test)

A Stroop test presents an object with two attributes – for instance a printed word which has 1) a colour font and 2) a meaning. The participant is then asked to name one of the attributes as quickly as possible, and the time taken to name it – the reaction time – is recorded. Such naming is easier to execute in quick time if the two attributes are ‘congruent’ rather than ‘incongruent’. So, using the example above, suppose the participant is asked to name the colour of the font. If the printed word “red” is coloured in a red font – “red” – the two attributes are congruent, meaning that “red” will be named relatively quickly. However if the word is “red” is printed in green font – “red” – it will usually take a participant longer to identify its colour as green, showing up as increased reaction time in response to such incongruent attributes. In short, the more one attribute interferes with another, the longer it will take to name it (reaction time).

For this paper’s experiment, the two attributes under manipulation were ‘taste’ and ‘musical interval’. In the words of the authors: “Four selected tone intervals (seconds and thirds) were presented while applying four differently tasting solutions (sour, bitter, salty and sweet) to E.S.’s tongue. Her task was to identify the tone intervals by pressing a particular button for each interval on a computer keyboard. Reaction times and errors were measured for trials in which the applied taste was either congruent or incongruent with the tone interval; tone intervals were also presented without taste stimulation”.

In order to investigate whether the ‘concept’ of tastes, rather than tastes themselves, could be employed as an effective attribute in the Stroop tests, trials were also carried out in which the ‘tastes’ were presented only visually (in word form), rather than as actual tastes on the tongue.

Five non-synaesthetic musicians (controls) were put through the same test procedure, still using E.S.’s taste-interval chart to define ‘congruent’ and ‘incongruent’ trials.

Results

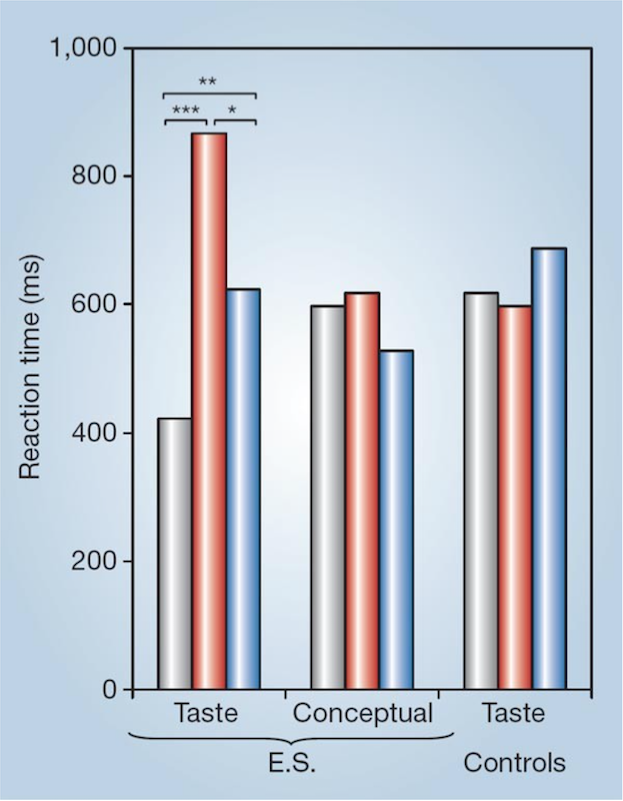

“E.S.’s tone-interval identification was perfect and was significantly faster during the congruent condition [in which the taste on the tongue matched, according to E.S.’s table, the interval presented] compared with all the other conditions.”

In contrast, the non-synaesthetic musicians (controls) were no faster in reacting to ‘congruent’ trials than to ‘incongruent’ trials.

When a musical interval was presented alongside drops of no taste on the tongue (hence the stimulus being neither congruent nor incongruent), E.S. and her non-synaesthetic fellow participants all displayed similar reaction times.

E.S. was asked also to undergo extra trials – called ‘conceptual’ trials – in which tastes were presented in word form, not as genuine tastes. Under these conditions congruent trials elicited the same reaction times as incongruent ones.

Here are the results in graph form:

Discussion

According to the authors: “Together, these results indicate that E.S.’s performance in the gustatory [taste] Stroop task is most likely to be due to her extraordinary type of synaesthesia, in which a complex inducing stimulus [hearing a tone interval] leads to a systematic, concurrent gustatory [taste] sensation.” Generalising further, they also claim “E.S.’s application of her synaesthetic sensations in identifying tone intervals — a complex task that requires formal musical training — demonstrates that synaesthesias may be used to solve cognitive problems.”

Coda

“Coffee Cantata” BWV 211 by J.S. Bach

Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra and Choir, conducted by Ton Koopman

I find this experiment a bit difficult to take seriously. One of the curious things is that the subject labels the Tritone as “disgust”, which is not an identifiable taste. The tritone has long been associated with dissonance in music and even called the Devil’s interval. And the long history of the interval likely presets a distaste for if. Anyone with some musical knowledge can identify intervals by sound. And since the subject’s synaesthesia is conveniently “one way”, there really is no way to truly ascertain that this phenomenon is not affected by the individual. The descriptions of the tastes much too perfectly align with normal sensibilities about major, minor, and close intervals.

In summary, I find this hard to swallow.

Hi James, thanks for the comment – and especially the summary! Maybe the authors put ‘disgust’ in quotation marks for that reason? I agree that the boundary between cross-metaphor and synaesthesia is tricky, and that the restless tritone is like the ‘kiki’ compared to the ‘bouba’ of the major third (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bouba/kiki_effect). I would definitely look to someone like Ramachandaran for more insight, e.g. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Edward_Hubbard/publication/237244759_People_with_synesthesia-whose_senses_blend_together-are_providing_valuable_clues_to_understanding_the_organization_and_functions_of_the_human_brain/links/0c960528a3f0979c4f000000/People-with-synesthesia-whose-senses-blend-together-are-providing-valuable-clues-to-understanding-the-organization-and-functions-of-the-human-brain.pdf.

I recall reading an article that attempted to show that Western music contained universally recognizable emotional qualities by playing movements of Beethoven and showing drawings of faces with emotional expressions to indigenous tribal people with no interaction with western culture. They were able to choose “correctly” what the music was suggesting, which validated the experiment, in the experimenter’s eyes. The trouble I found with this “study” is that the images very likely steered the subjects in ways they would not have come to without them. Personally, I do not assign imagery to music, finding the sounds engaging enough on their own. A friend once said that he got the sense of drifting in a small boat on a foggy primeval waterway when he heard the opening of the second part of Stravinsky’s Sacre du Printemps. I could see how one could make such a connection. But I would not have done so without the suggestion. The trap of suggestion, I feel, tainted the experiment. Lutoslawski put it well when he stated in an interview that “the only unambiguous message that music can, in itself, convey is a musical one”. I do not subscribe to the notion that music communicates unequivocally to all humans. It does not for me. The music that moves me does not appeal to many traditional classical music lovers. That most listeners believe that “music” is defined only by Major and minor triads and melodies that fall within that harmonic structure does not prove the supposition. It is the universality of media reinforcement that cements that belief. Put the music of Henze, Lutoslawski, Berg, Birtwistle, Carter on and they run screaming from the room. That’s not music! Universal, my foot.

I realize I have digressed far from the topic of synaesthesia, but that Tritone designation got my dander up. Is dissonance still the work of the devil? Come now. Simple tonal music inundates modern life, from our ring tones and sounds our laptops make, to the constant barrage of triads emanating from stores, inside and out, to everything the mainstream media focuses on. The tonal indoctrination is so complete that E.S.’s is unaware how it dictated her cross-metaphoria. No summary this time.

Hi James, I hope today’s post will relax your dander, suggesting as it does that Western music is not a universal language. I’d be interested to hear your thoughts. Meanwhile I hope and trust you have a circle of friends who do not run screaming from Henze, Lutoslawski, Berg, Birtwistle and Carter; I did once have an audience member leave during a Xenakis duo, but I would describe it as huffing and puffing more than screaming.